Is there a sustainable future for tourism?

We all get wanderlust sometimes. But, given the climate crisis, we may have to rethink the way we hop across the world.

Last year, a record 1.4 billion tourists made international arrivals at the world's airports. Then, in 2020, the booming business of travel crashed.

Over the first six months of this year, the industry lost US$460 billion in revenue—five times more than was lost due to the 2009 economic downturn. It's all due to the coronavirus, of course, which caused many countries to shutter their borders. Now, places that have built their economy around tourism are suffering even more than the rest of the world.

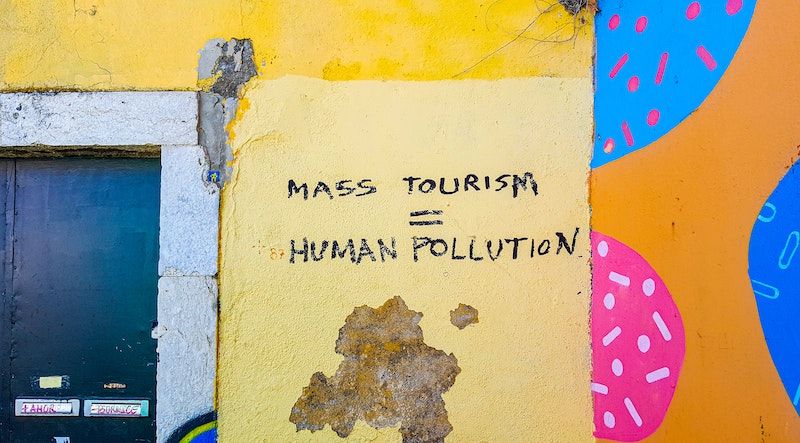

Ironically, just a few years ago, some places were facing the opposite problem: overtourism. The presence of too many tourists sparked protests in a few popular cities in 2017. Venice, most famously, has been nearly smothered under the weight of 30 million visitors a year.

Is there a way to fix this this broken industry? Many people are attempting to establish structures that would allow for sustainable tourism—which, as defined by the UN's World Tourism Organization, aims protect a wide range of resources: preserving local cultures; expanding local economies, thereby alleviating poverty; and protecting the environment, too.

Is that really possible? Accomplishing it all in the age of climate change is going to be challenge.

📚 Jump to section:

What is overtourism?

Lately, as the global middle class has grown and as budget airlines have brought down the cost of flights, long-distance travel has become increasingly accessible. And isn't travel a good thing? For many people, a passport full of exit stamps is a badge of honor—a symbol of worldliness.

Certainly there are economic upsides, at least for popular destinations: Travel brings in money and creates job. Given that most tourists are economically privileged, and that many popular destinations are in developing countries, tourism has been called a voluntary transfer of wealth from the global rich to the poor. Tourism dollars are particularly essential for some conservation projects—which has made this travel-free year devastating for certain endangered species.

This is not the most efficient form of wealth distribution, though. There's a lot of leakage: Some of the dollars tourists spend are soaked up by international corporations like hotel chains. In some small countries, even the jobs themselves are sometimes outsourced to foreigners.

Tourism can help move money from richer to poorer countries, though there's a lot of leakage, as big corporations soak up some of the profits.

The influx of people also puts pressure on infrastructure and resources. Where does all the trash go? (As it's become increasingly easy to buy your way up Mt. Everest, a former symbol of wilderness has become littered with the refuse from former expeditions.) Where does the water come from? (In Cyprus, a single golf course may use as much water in a year as a thousand local residents.) Can the ecosystem handle the traffic? (A popular tourist beach in Thailand had to be closed after 80% of the local coral reef was killed.)

Tourism can also lead to a kind of gentrification: Businesses are built to cater to visitors, not to locals, while the cost of living rises. In 2017, protests in Venice focused on the rising cost of rent, which was largely attributed to short-term vacation rental companies, like AirBnb: Home owners decide to rent to tourists, rather than residents, which restricts the supply of housing stock. At their most reprehensible extreme, these same economic forces can lead countries to displace Indigenous people for the sake of "ecotourism."

What is the carbon cost of travel?

Over-travel is not just a problem for destination countries. To carry hundreds of people over thousands of miles, airplanes burn enormous amounts of fuel—which means a major impact on the climate.

Airlines are trying to be more fuel efficiently—by cutting excess weight, for example—but over the past few years the rate of passenger-miles has been growing faster than innovation can keep up. So even as individual flights get slightly cleaner, the industry's overall contribution is still growing. A recent study in Nature found that tourism accounts for 8% of global emissions, with air travel being the major culprit within the industry.

Those numbers could well be an underestimate: The study did not factor in the effect of contrails, those little wispy clouds that trail in the wake of airplanes, which have their own substantial greenhouse effect. Precise per-mile emissions are hard to calculate, as they depend on many variables. In some cases, flights may actually be more efficient than a single-passenger car. But the problem with flights is really "hypermobility": They are fast, which makes it easy to travel thousands of miles. You simply cannot get from New York City to Seoul by car. Flights allow us to jet across the world for vacations, or hop on short flights to travel to business conferences, crisscrossing longer distances than we ever would without such technology.

How can I be a more responsible tourist?

A number of different organizations will steer you towards specific hotels and destinations that have embraced the concept of sustainability. Generally, though, a bit of common sense, alongside a strong dash of respect, can go a long way.

Choose a destination that isn't already overtaxed by visitors, and once you're there, do whatever you can to make sure your money goes towards local businesses, rather than big corporations by choosing locally owned restaurants and shops. (When it comes to hotels, though, a locally owned boutique hotel in a tourist district may be a better choice than an AirBnb in a residential neighborhood. As noted above, short-term rentals have driven up the cost of living for locals in many destinations.)

Learn enough before you arrive so that you can greet people in their local language, and so that you understand the standards of etiquette. Dress in ways that are considered respectful. Don't treat locals as just a part of the scenery, something to ogle; get to know someone before you snap their photo. And go light on resources like water and electricity, wherever you are.

An easy and important solution is to be respectful and kind.

To reduce your climate impact, once you're at your destination, rent bikes or use public transportation to get around, if possible. Of course, getting to destinations is a major source of the problem. What can you do to make up for that fact?

Is it possible to reduce emissions from flights?

Long-term, there may be methods that help make flying less carbon-intensive. There is already work underway on small electric and hybrid planes. Hydrogen may also work as a cleaner fuel source, though it's quite expensive. Within the industry, people seem to believe cleaner flights are still at least 15 years out. For now, then, if you really need to cover long distances, trains are your best bet.

The hard truth is that for the time being, if you are serious about reducing your carbon footprint, you may have to rethink your relationship to mobility. A cultural shift may be on the horizon; in Sweden already there is an emerging idea of "flygskam," or flight shame. For those who prefer the carrot to the stick, consider the corollary concept of "#tågskryt"—the "train brag," which is used on social media to show off low-carbon travel.

Perhaps this year's tragic pandemic can have a small upside. We've had to reorganize our relationship to the physical world. We've already learned to work remotely; business conferences, too, can be conducted digitally.

Still, those of us who travel for pleasure will have to find new ways to fall in love with our home turf. Part of the satisfaction of travel is the feeling of getting away—putting some distance between yourself and your workaday world. Is it possible to rethink what distance means? Can a slower trip by train or bike help you feel far away, even if the physical distance is less? Is there a place nearby that seems to offer some cultural distance from your home neighborhood?

There's more to the world than we know. For years, that's motivated many of us—myself included—to wander the far corners of the world. Now, though, it's time to dig in and find the mysterious and delightful in our own backyards.