The promise of wind power

Can we depend on wind power? We have to.

Last week, amid widespread power outages across Texas, a lot of blame was placed on frozen wind turbines. Some turbines were frozen, which reduced the amount of power reaching the grid—but really this was a minority contributor to a complex problem.

The brouhaha was a reminder of how contentious "windmills" can be. For decades, offshore wind farms were stalled in the United States, in part because of strident opposition: Turbines are too ugly, people said, and too deadly to birds.

Nonetheless, wind is now a proven source of power—an essential tool as we decarbonize our economy. It's here to stay, assuredly, though there are issues to address. Here's the rundown.

📚 Jump to section:

How does wind power work?

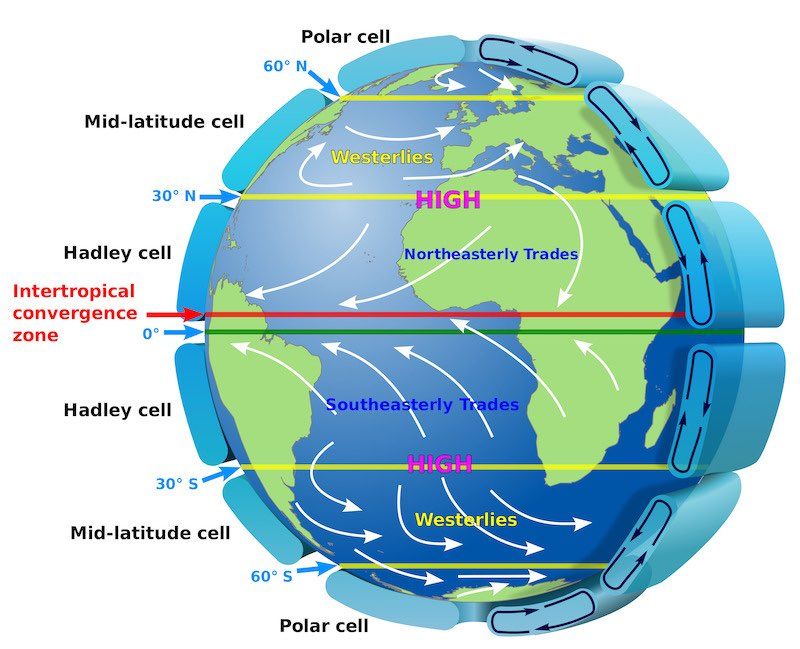

Let's start with simple laws of physics: Because the Equator gets more sunshine—and therefore more heat—than other parts of the globe, it has a lower atmospheric pressure. This help drives global wind patterns, which flow from areas of high pressure to low pressure.

Human beings have exploited this fact to push sailboats for at least 7,000 years. By 200 BC, cultures across the world were using wind to pump water and mill grain.

The first successful wind-powered generator—which, much like today's plants, used wind to spin an electromagnetic turbine that converted kinetic energy into electricity—was built by a British professor in 1887. The turbine stood in the garden of his holiday home and powered its lights. (He offered to power lights along the main street of the surrounding village, too, but his neighbors thought electricity was "the work of the devil.")

A modern wind farm needs average wind speeds of 13 miles an hour—though new turbine designs will decrease the necessary speed, expanding the availability of wind power.

The word "windmill" is often mistakenly used; today's wind turbines don't actually mill anything. Almost all share the same design: it's called a "horizontal axis" turbine, and features three blades atop a tower, all set on a concrete pad. The size of the turbines can vary; in the U.S., the average turbine is around 280 feet tall.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, a modern wind farm requires average wind speeds of 13 miles an hour (5.8 meters per second). Gaps in mountains that funnel winds are good settings, as are higher elevations generally. Offshore sites are also a good choice, as there are fewer obstacles to slow the wind. As technology improves, the necessary wind speeds have been decreasing, opening up more potential sites. (As for cold weather: heaters are regularly to de-ice turbines, but were not installed in Texas.)

There is one major challenge still: when the wind is not blowing, no power is generated. The "capacity factor" of a wind farm indicates how much its potential power is actually produced. Across the U.S., the current average capacity factor is around 35%. Capacity factor tends to be higher for newer wind farms, though, thanks to design improvements.

What role does wind power play today?

Wind power was used at a small scale throughout the twentieth century in Europe and the U.S., but it really took off in the 1970s, amid a global oil crisis. Onshore wind came first, but by the 1990s the first offshore projects appeared in Europe. According to the Global Wind Energy Council, offshore projects accounted for 5% of global wind energy supply as of 2019—though they made up 10% of the new projects built that year.

Solar and wind power are now the cheapest form of electricity for most people in the world.

Offshore was particularly slow to arrive in the U.S. In 2001, a company proposed building a farm off the coast of Massachusetts, but the project met significant opposition. The first U.S. utility-scale offshore wind project was not completed in until 2016. (It is in Rhode Island; a second offshore farm, in Virginia, came online in 2020.)

Last year, Bloomberg noted that onshore wind (alongside solar) is the cheapest source of power available to most people in the world. Offshore wind power remains pricier, though there are some European markets where it is competitive with other forms of energy. In the U.S., the "levelized" cost of offshore wind power—a figure that factors in lifetime investments, including facility construction and decommissioning—is still more than three times higher than for onshore farms.

Are there any drawbacks?

Wind power has its share of critics. Donald Trump frequently rails against turbines. Before he became, Trump president sued the Scottish government in an unsuccessful bid to stop a wind farm from being built offshore from one of his golf courses.

The major point of opposition is aesthetics: People don't want massive, industrial devices cluttering the landscape. Though even when the infrastructure will be invisible, this opposition sometimes persists. In the U.S., for example, one wealthy community is opposing a project due to fears that a buried cable might carry health risks, though the science does not support their fears.

The major point of opposition is often aesthetic: people don't want big, hulking, industrial machinery in their backyards.

NIMBYism, this is sometimes called: "not in my backyard." There are more principled reasons for opposition, too: Some proposed wind farm locations would intrude upon sacred Indigenous spaces or alter important fisheries. Wind farms also take up more space than other kinds of power plants, though they onshore wind farms can double as actual farms, with crops growing between turbines.

As I noted above, the intermittent nature of wind power (and solar) does mean that the grid will need some other supplement—perhaps a new generation of nuclear plants, or perhaps a network of battery-storage centers. One thing the Texas outages make clear is that our current grid is not ready to for our climate future.

What about the birds? Hundreds of thousands of migrating birds do die each year due to collisions with windmills, but many conservation groups have noted that the effects of climate change will be far worse for birds—and therefore support wind power, so long as the turbines are properly sited. There are emerging solutions, too, sometimes quite simple: A recent study found that painting one blade black can reduce bird mortality by 72%.

What's next for wind power?

Most forecasters predict ongoing growth for wind power across the world. And the U.S. may soon become a global leader: One of President Joe Biden's first executive orders halted called for a doubling of offshore wind power within the next ten years. (A few years ago, the Department of Energy suggested that 20% of U.S. electricity could be supplied by wind power by 2030, and 35% by 2050; as of 2019, wind made up 7% of of U.S. electricity.)

One of Biden's first executive orders called for a doubling of U.S. offshore wind capacity in the next ten years.

Within the next few years, capacity factor for U.S. offshore farms is expected to rise above 50%. Already, costs are falling—dropping by two-thirds in the past eight years. Companies are pursuing new technologies, including ever-larger turbines—nearly 900 feet tall, in some cases—and floating platforms that can sit further out at sea. Windmills may be a classic sight, centuries old, but they are liable to continue to evolve as we create a better future.