What do projections say about the future climate?

The worst-case scenario now seems unlikely. But don't breathe easy yet.

It is perhaps the most fundamental question posed by climate science: just how hot will the world get?

Given what's happened over the past few decades, the scientific consensus has lately converged on one number: we can expect 3°C warming by century's end. That's far from the worst we once imagined—but it's also far from good. Here's what that number really means.

📚 Jump to section:

Where do climate projections come from?

Before we look at the numbers, it's worth understanding how they're calculated.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, created by the United Nations, produces an ongoing series of studies, and every few years combines these into an overarching "synthesis report." These reports are compiled by thousands of scientists, and are considered the gold standard in climate science. The latest synthesis report, the fifth, was released in 2014.

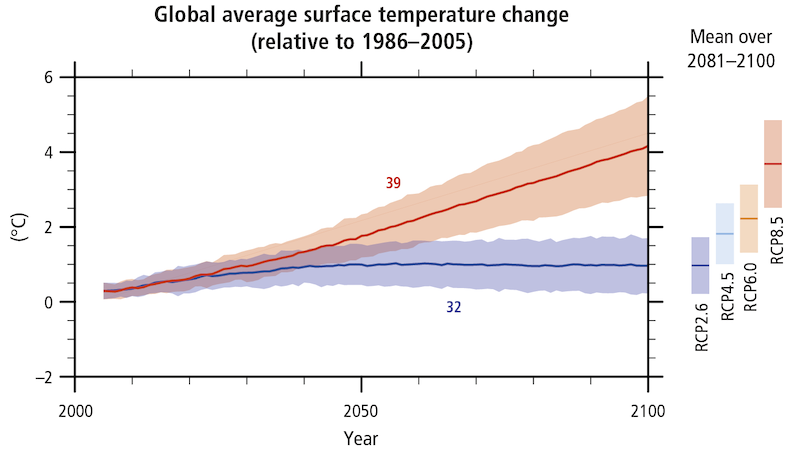

The 2014 report offered not just one prediction of where the climate was headed but four. These were called "Representative Concentration Pathways," or RCPs. Each RCP assumes a different amount of emissions might reach the atmosphere; researchers, using models, then calculates the resulting temperature rise.

The best-case scenario was called RCP2.6. In this scenario, emissions are strictly limited, and eventually turn negative—which would require that we find effective ways to remove large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere. The worst outcome, meanwhile, a world of skyrocketing carbon use, was labeled RCP8.5.

In between are two moderate pathways, RCP4.5 and RCP6. (The numbers indicate the extent of "radiative forcing" in 2100; think of this, basically, as how much worse we wind up making the greenhouse effect.) These four RCPs are referenced in nearly every scientific paper that considers our climate future.

The next 15 years are set...

In the short term, all four RCPs offer consistent outcomes: no matter what actions we take, we're likely to see a substantial rise in temperature over the next 15 years.

Across all four RCPs, global temperatures through 2035 appear to be 0.3° to 0.7°C higher than they were in the 1980s and 1990s. That's because carbon, which stays in the air for centuries, takes a while to enact its toll. The temperature rise we'll see over the next few years is result of what we've already emitted.

...but then things diverge

As we barrel towards mid-century, though, the effect of new emissions racks up.

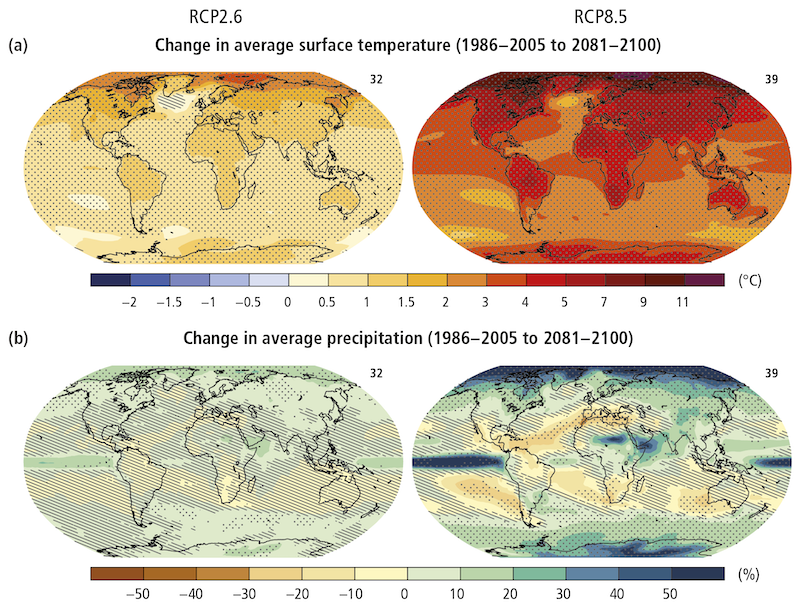

The graphs above show the full potential trajectories for RCP2.6 and RCP8.5 through 2100. (The 2100 outcomes for the two mid-level pathways can be seen to the right of the graph.) Temperature rise might be as low as 0.3°C or as high as 4.8°C. It's also worth noting that these numbers indicate average rise across the globe. As the maps below indicate, warming in some regions will be much higher.

So what path are we following?

The key question, now that we're six years past the latest IPCC report, is what track we've been on. Often, the grim case of RCP8.5 is presented as the "business-as-usual" scenario—that is, where we're headed, given what we're doing now.

Scientists, though, decry such depictions. RCP8.5, some say, is and was always a worst-case outcome. In fact, to reach the level emissions included in RCP8.5, coal use would likely need to increase five-fold in the coming decades. That not only goes against current trends, it may well be impossible, given how much coal exists on earth.

Sometimes it is good to prepare for the worst. The trouble with emphasizing RCP8.5, though, comes when it's only compared to the other extreme. The graphs above, for example, imply that we will either head towards 5°C of warming or we'll mostly hold things in check. The most likely scenario is the least discussed: that we'll land somewhere in the middle. And in this case, the middle is no good.

A 3° world

Lately, some scientists have adopted a clean, round number as the best guess for future warming: we can expect 3°C of warming by 2100.

There is still a range of possibilities, of course. In preparation for the next IPCC reports, a group of scientists have refined our understanding of "climate sensitivity," which estimates the impact of carbon on temperature. Their new figures suggest the range of warming is between 2.6°C and 3.9°C.

The new 3°C prediction is not only due to new data. It also has to do with changing policy: We are no longer in a world where emissions are simply growing unabated. Our climate projections can and do increasingly consider the government programs already launched, as well as those soon to be launched, and assess how these might impact warming.

Compared to 5°C, this update may sound nice. It's not nice, though—3°C of warming would be a catastrophe. Cities now home to a collective 275 million people would find themselves underwater. There would be mass extinctions. Much of the planet would turn uninhabitable.

The next projections

A new IPCC synthesis report is due next year, and it will introduce a whole new set of terminology. RCPs are out, and now there is instead a new acronym: SSPs.

This stands for Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. The RCPs simply assumed an certain amount of emissions might be released, and studied the results; the SSPs, meanwhile, offer a story of how we we might reach each emissions scenario, politically and economically. What happens if an explosion of nationalism causes countries to focus on their own security, rather than collaboration? What if the world steadily commits to more education and less inequality

These and other questions are posed, and the potential answers inform the new models being developed. The statistical science behind the SSPs has already been set, and the new IPCC report will include five different pathways. One can only hope that, as the potential stories of our future climate come into increasing clarity, the knowledge will lead us down a better road.