What is the state of global climate policy?

There are plenty of tools available to address the climate crisis. The obstacle, for now, is getting politicians to pick them up and put them to work.

2020 feels like the year of the unexpected. One outcome that would've been hard to predict just a few years ago? A sudden dip in greenhouse-gas emissions. That's due to the coronavirus and its impact on the global economy—and tragedy, of course, is not the way we want to solve the climate crisis.

Still, there is a lesson to be learned learn from this year. The world is capable of scrambling to solve big problems—and we have the money to get it done. In fact, if the world took just just 10% of the stimulus funds that have already been committed to coronavirus recovery, we would be able to get on track to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

It's not just the money that's out there. Clear policy tools exist, too. Let's take a look at what those are—and where they're actually being put to work.

📚 Jump to section:

What's in the toolbox?

Policy makers divide their toolbox into two big sections. First, there are market-based tools—those that steer behaviors by altering economic incentives—and then there's everything else.

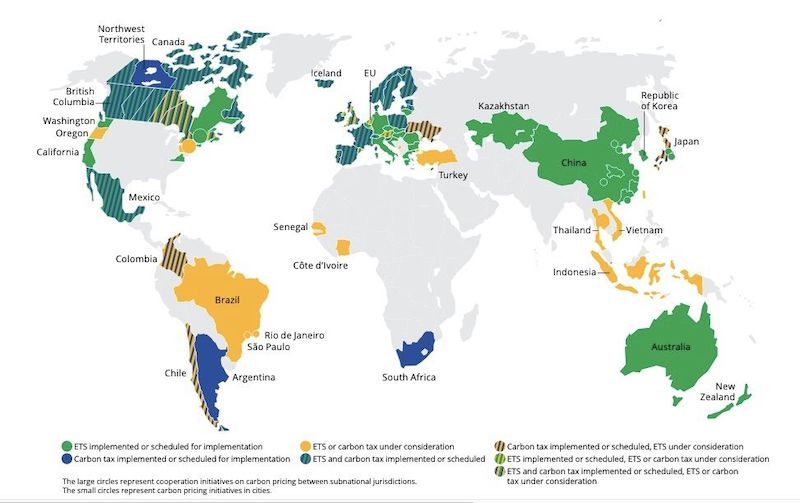

Market-based policies typically put a price on carbon. The idea is that when we pay for a fuel—or a refrigerant, or for any other greenhouse-gas emitting product—we should be paying, too, for any long-term costs that accrue to society. I've written before about the two major approaches: First, carbon taxes, which consist of an extra price tacked onto carbon fuels, collected by the government. The second idea, emissions trading (sometimes called "cap and trade") is slightly more complicated. In this system, you must have a permit for each ton of carbon dioxide you emit. There are only so many permits available, and that means permit holders who find ways to reduce their emissions can sell off their permits and thereby profit.

It's also possible to intervene in the market: Governments can provide research funding in an attempt to help private companies get through the expensive R&D stage, or can offer tax subsidies that entice consumers to move towards cleaner technologies.

Non-market-based policies are sometimes called the "command and control" approach, since they consist of a top-down dictate to do what you're told or face a legal punishment. Performance standards are a common example: A law can require all cars stay below a certain fuel-efficiency rate. There are also technology standards, which dictate that certain technologies—coal plants, say—are out of bounds. The objection to command-and-control tools is that they can be more expensive than a market-based approach. That said, they also tend to be smaller, and able to target particular sectors of the economy.

It's worth noting that the above policies focus on climate-change mitigation. There is a whole separate suite of policies available to address climate adaptation, some of which we have covered before.

Is there an overarching structure guiding global policy?

Yes. Every year, members of the United Nations participate in meetings called Conferences of the Parties, or COPs, where climate treaties are developed and refined. Early on, countries agreed that everyone should be responsible for their "fair share" of the solution. That means countries that have historically emitted the most must now take on the bulk of the world's emissions. Indeed, some countries where emissions have been historically low have been allowed to increase their emissions under global treaties.

Most UN members are party to the Paris Agreement, which requires that national governments set a targets for emissions reductions and then develop plans to meet that target. The Paris Agreement, as I've written about before, is fairly toothless: There is no punishment for failing to follow the plan.

There is a global order here, but the Paris Agreement is mostly toothless. Its greatest advantage is that it allows us to evaluate countries' performance.

What it does, though, is give us the chance to assess the extent to which the world's governments is taking this problem seriously. So let's go for a tour.

The Americas

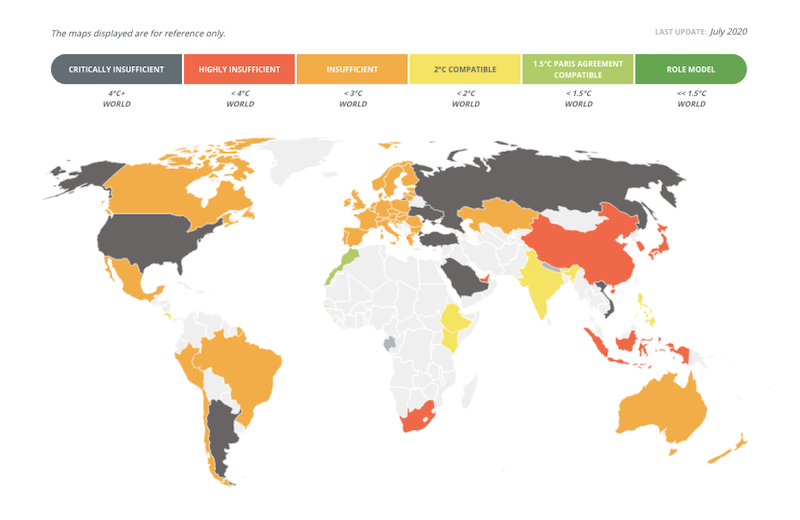

A key resource for understanding global climate policy is the Climate Action Tracker (CAT), a partnership between two research agencies that analyze countries' plans and monitor whether they are actually following those plans. The CAT focuses on a handful of the world's highest-emissions countries; each is given a label that assesses whether they are meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Canada, Mexico, and Brazil are among top 20 highest-emission nations and according to the CAT all three are pursuing "insufficient" policies. (This, sadly, matches the the global status quo; "insufficient" is the most common label.) Mexico and Canada do have market-based carbon pricing mechanisms, but these have not yet had a major impact.

Politics is a key barrier. In Canada, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has promised to pursue more rigorous action to stop climate change, but his party no longer holds a majority in Parliament. In Brazil, meanwhile—home of the Amazon, an essential global climate sink—President Jair Bolsonaro has begun to pursue an aggressively anti-environmental platform.

Bolsonaro is often compared to his friend, United States President Donald Trump, who has said that global warming is a "hoax." The U.S. is one of the world's highest-emission countries—only China is higher—but has no carbon pricing policy in place and is making no broad effort to increase the use of renewable power. Trump has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement, too. The CAT scores the U.S. as "critically insufficient." Perhaps this will change soon; president-elect Joe Biden plans to re-enter the Paris Agreement as soon as he takes office in Janurary. But he too will face a opposition majority in the Senate, which may limit his approach.

Europe

Almost every country in Europe is a part of the European Union, which drafts a single, joint plan for the purposes of the Paris Agreement. The EU manages the world's largest emissions-trading program, which has produced positive if modest results. Overall, though, the CAT finds the EU's policies insufficient.

The future does lok bright. In late 2019, the EU announced its commitment to the "European Green Deal." This initiative aims to achieve net-zero emissions across the EU by 2050, and will require overhauling most of the continent's current energy and climate legislation. The specifics remain murky, but across the political spectrum, parties in Europe's largest countries seem to agree that ambitious efforts to decarbonize the economy are essential.

The Russian Federation does not only have dangerously weak climate policies—it is also complaining about the local impact of the EU's policies, effectively attempting to dismantle efforts abroad.

To the east, in Russia, there is less good news. Though it is among the world's highest-emission countries, Russia has set Paris Agreement targets so low that it will be able to meet its them without taking any action. (The CAT, unsurprisingly, calls these policies "critically insufficient," the worst possible ranking.) The country has also complained to the World Trade Organization about EU efforts to impose a carbon border tax—which would apply to Russian imports—essentially undercutting its neighbors' attempts to solve this problem.

Asia

Saudi Arabia has the highest per-capita rates of emissions in the world, and its current climate policies are critically insufficient. Perhaps this is unsurprising: The country's economy is built on oil and, despite a nominal plan to increase its use of renewable electricity, its leadership has shown little interest in diversifying.

Across much of the rest of the continent, coal is the center of the story—especially coal in China. Though its per-capita emissions rates are fairly low (a third of Saudi Arabia's), China has a massive population; this makes China the world's highest-emission country by volume.

A month ago, China announced its intention to go carbon neutral by 2060. This will be achieved largely through a rapid ramp-up of renewable energy, and would constitute a major change; as of just a few months ago, the Chinese government has been greenlighting coal plants at an alarming rate. (The country is already the world's leading funder of coal plants, with investments supporting plants across the world.) There are few details about the national emissions-trading scheme that was supposed to launch this year—and would immediately be the world's largest. The question now is whether China stick to its new commitment.

A few weeks ago, Japan also announced its intention to go carbon neutral. It's not clear that its 2050 goal is truly feasible; like China, Japan has long been reliant on coal and has not followed through on past policy goals.

Meanwhile, India, the world's third-highest emission country, has been increasing coal production—which is part of why the country's emissions are rapidly increasing. Ironically, the CAT scores India's policies as compatible with a 2°C world. That's in part because India's historic emissions have been so low. Under the "fair share" doctrine, the country still has room to grow.

Oceania

The island nations of Oceania have small populations, and even combined they have a relatively small impact on global emissions. Still, Australia has a very high per-capita emissions rate—higher than the U.S.'s, in fact—and the government has made no attempt to address that fact. Australian leadership has embraced a "technology neutral" approach, which means, really, continuing the status quo—which is heavy on fossil fuels. New Zealand, in contrast, has a rare legal commitment to zero emissions. Nonetheless, the country has enacted few policies to pursue this goal.

Africa

Thanks to its equatorial location and its high rates of poverty, Africa is going to be harder hit by climate change than any other continent. And only one country sits on the list of the top 20 emitters: South Africa. (Its leaders have begun to shift away from coal power, though official emissions targets remain weak.) For other governments, adaptation is as much the focus as mitigation.

Nonetheless, the only two countries that have been deemed by the CAT to be pursuing policies compatible with a 1.5°C world are in Africa: Morocco and the Gambia. That's in part due to the "fair share" doctrine; both countries' policies will actually marginally increase their emissions in the coming years. Still, there has been a substantial push towards carbon-free energy. Morocco is home to the world's largest concentrated solar power plant, and the Gambia is pursuing a major solar plant.

Who will take responsibility?

I have to admit that I as compiled this global survey, I found the results rather depressing. The countries that most need to tackle this problem are kicking the can down the road—or even standing in the way of progress. Global warming is, well, a global problem—so it will be nearly impossible to address if leaders care solely about short-term benefits for their own citizens. That said, politics can and do change, as the recent U.S. election has reminded us all.

On a brighter closing note: I've focused here on national policies, but the biggest breakthroughs have often come on the sub-national level. Cities, states, and provinces—and businesses, too—have stepped up to fill the gaps. That can't be the full solution. But at least it gives us a model for what future national and international approaches might look like—and a fighting chance to keep emissions at a manageable level until the world wakes up.