Your support stops illegal logging in its tracks

San Fernando patrollers catch illegal loggers red-handed and put a stop to their harmful activities.

Just the gist

Short on time? Here’s what you need to know for this update:

- 🪵🪓 Community monitors stop deforestation in its tracks — San Fernando patrollers catch illegal loggers red-handed and put a stop to their harmful activities.

- 👩🍼 Expanding women’s participation in rainforest protection — Overcoming barriers by implementing childcare and reducing stigmatization against women in the field.

For more project updates, follow Wren on Twitter and Instagram.

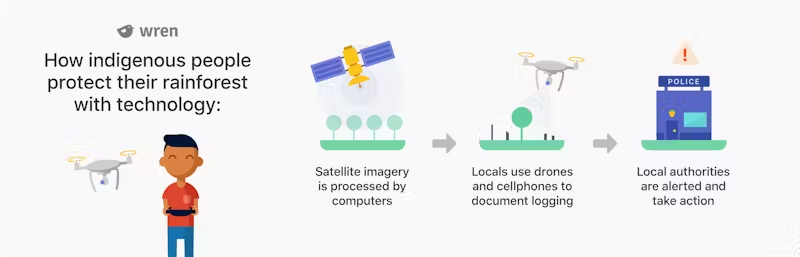

Community monitors stop deforestation in its tracks

In San Fernando, a community in the Alto Napo region of Peru, community monitors discovered that loggers were illegally deforesting an area that belonged to their neighboring community, Sumac Allpa.

The monitors confronted the loggers and forced them to leave, an intimidating but necessary task to protect the rainforest. Later, they informed Sumac Allpa and provided photographic evidence of the deforestation. The likelihood of illegal actors returning to an area is drastically reduced if they are aware that the community's forests are being monitored.

The Rainforest Alert program is a lot like a local neighborhood watch, where the community comes together to reduce incidents in their area. But in this case, the local area includes thousands of hectares of Amazon rainforest. To protect their land, wildlife, and livelihoods, a network of community monitors can control access to rivers that lead deeper into thickly forested and uninhabited areas.

Monitors will often join forces and approach illegal actors in their territory as a group. This solidarity makes the confrontation safer than approaching alone or in small numbers. It also promotes a spirit of shared responsibility for the wellbeing of the larger forested area.

Monitors also share best practices and learn from each other, which helps expand the program faster. This train-the-trainer approach ensures that the program is not seen as a foreign-imposed intervention, rather a local solution that communities are proud to participate in.

Expanding women’s participation in rainforest protection

Our project partner recently carried out a study in Ucayali and Loreto provinces to evaluate the participation of women in common spaces and in forest monitoring work. The result showed that few women were able to participate in the training because they had to take care of their children and their households.

Betty Rubio’s grandmother was the first to teach her respect for the forest and that forests are disappearing everywhere.

“I used to sit with her when I was little, and she would tell me what nature was like when she was my age and why it was disappearing.”

Betty Rubio Padilla, an indigenous forest patroller in Puerto Arica, Peru

Women in her community carry and pass down the knowledge of how to take care of plants, and use them to save someone’s life, so why aren't more women in community assemblies and decision-making spaces? Involving women in programs like Rainforest Alert is important, since deforestation affects them too.

Stories like Betty’s inspired our project partner to take action, creating equal opportunities to join learning spaces. The first step was to provide and coordinate shared childcare during assemblies. As a result of this simple measure, more and more women are able to learn about forest surveillance, confident that their children are cared for during their training.

But childcare isn’t the only challenge preventing Indigenous women from joining the front lines. “There is a lot of stigmatization about what a woman should do within the community, and field work was frowned upon because it was considered men's work,” adds Kathya Castillo, a specialist in Peru.

Our project partner currently has 16 women as local monitors. In five participating communities, some of these women work alongside a spouse or family member, so their participation is socially accepted.

“If the women cannot enter the forest, they can receive the information that comes from the field and organize it into files or manage the work teams. If the couple supports us, this can be achieved. You have to understand that this is no longer just a job for men.”

Betty Rubio Padilla, an indigenous forest patroller in Puerto Arica, Peru

Last summer, funding from Wren members helped to train 38 new Indigenous monitors, including nine women. These efforts decreased local deforestation by 84%, which is fantastic progress, but the fight isn’t over yet.

So far this year, our project partners have trained 24 monitors from 10 new communities, and they plan to expand to 28 additional communities over the next few months. During training and community meetings, they will provide meals and offer childcare to ensure that everyone, regardless of gender identity and social stigma, has the opportunity to take part in the program and defend their territory.

With additional funding from Wren supporters, like you, they anticipate to expand their work with many more communities.

That's all for this update! As always, thank you for your support.

— the Wren team 🧡